I read The Limits to Growth recently, and I was surprised to find almost none of the criticisms regularly leveled at the report have any substance. I guess if you prefix a piece of research with the words ‘now discredited’ enough times, eventually even the smartest people will follow suit.

Here are some of the accusations I’ve heard, and what the book actually claims.

The predicted crash by 2000 never happened

I’ve read a number of times that The Limits to Growth predicted a collapse of the industrial system by the year 2000. A decade on, cue much jeering from people who clearly haven’t read the book – it doesn’t put dates to a crash, but suggests growth cannot carry on beyond 2100. This criticism is a whole century too early, and I imagine it originated either as a lie or a typo. If economic growth is still flying in 2100, the report will be proved wrong, but this is the most nonsensical of the common objections.

Computer modelling is inherently flawed and unreliable

This is an argument familiar to anyone who’s ever heard a climate skeptic, and the same points are made in reference to The Limits to Growth. Considering this was done in the earliest era of computing, there’s no doubt that the model is oversimplified in places, but it depends what you’re expecting. Exact predictions are impossible from a model like World3, but the authors know this. They describe their process as “‘prediction’ only in the most limited sense of the word”.

The aim is not to predict exactly what will happen, but to show the shape of the future if current activity continues. They compare it to throwing a ball into the air. You couldn’t say exactly how high it will rise to the nearest centimeter, or what velocity it will attain on its way down, but you know what its basic behaviour will be: It will rise, arc, and fall. That is it’s ‘behaviour mode’, and that is what the computer model here aims to do for industrial society. What it suggests is that if growth is not managed, the general shape of the future is overshoot and collapse.

The report gets the dates wrong for resource depletion

Another regular criticism is that the book predicted the depletion rates of various metals, and got the dates hopelessly wrong. In fact there are very few dates in the book. As I described above, the report is concerned with general trends, and there are too many uncertainties to make specific predictions. The authors are adamant throughout that “the exact timing of these events is not meaningful”.

In the whole book, there is only one spread that contains specific dates. There’s a table that lists a series of non-renewable resources and the dates at which current stocks would be exhausted at current levels of consumption. It offers a range of dates allowing for future discovery or recycling. Copper reserves for example, either had another 21 years left to run, or 36 or 48, depending on the assumptions. That gives you 1993, 2oo8 or 2020. These aren’t predictions, but a range of depletion scenarios extrapolated from the consumption rates of the time.

Interestingly, in 2008 a research report compared the Limits to Growth models with “30 years of reality”, and found that “historical data compares favourably with key features of a business-as-usual-scenario”.

This graph, for example, shows aggregate non-renewable resource depletion (in purple) tracking pretty close to the Limits to Growth ‘standard run’ projection.

The model fails to anticipate technology

This objection emerged at the time of publication and has been repeated ever since, that the computer model doesn’t allow for advances in technology. This isn’t true. “Mankind has compiled an impressive record of pushing back the apparent limits to population and economic growth by a series of spectacular technological advances” say the authors. The technology component of the model factors in huge advances in nuclear energy, high-yield agriculture, recycling, and off-shore drilling, among other things.

Some critics suggest that the report assumes linear change, while technological change is actually exponential. There is something to this argument – the authors admit they struggled to find a suitable way to factor in changes that you can’t possibly foresee. But while this may extend the limits by a few years, it doesn’t change their fundamental conclusion that continuous growth can only end in overshoot and collapse.

The Limits to Growth is neo-Malthusian, and Malthus was wrong

I’ve read before that the Limits to Growth predicts a ‘Malthusian catastrophe’ by suggesting we’ll run out of food. And since the green revolution proved Malthus wrong, the conclusions of the Limits to Growth are also wrong. (I don’t understand the fixation with Malthus. It seems you can’t raise the possibility of food shortages without someone mentioning him, as if he’s the only person to have written about the topic.) The authors were well aware of the dramatic progress of the green revolution and discuss them in some detail. The computer model allows for similar advances into the future, and actually errs on the side of optimism. Like technology however, agricultural advances only buy us more time rather than change the eventual outcome.

The Limits to Growth supported industrial elites by calling for an end to change

This is a newer one, and perhaps not so common, but worth mentioning. It’s cropped up in Adam Curtis’ documentary All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, (see comments below) where he argued that The Limits to Growth supported the status quo of industrial capitalism when it suggested a steady state economy.”World governments should give up on the idea of promoting continual economic growth,” Curtis paraphrases, but then equates this to saying that politicians and governments “should give up trying to change the world” and instead, focus on managing the existing system. It may have been understood that way by some, but it would not be the view of the authors. “Global equilibrium need not mean an end to progress or human development” they write, and the last chapter argues for an ‘equilibrium society’ that is more equal and more free. It is true that they avoid politics, but it is certainly not a call to inaction. “A decision to do nothing is a decision to increase the risk of collapse”, they say.

In conclusion

The Limits to Growth has been badly misrepresented, which is suppose is inevitable after almost 40 years of telling people something they don’t want to hear. Reading it now, what surprises me is just how few claims the authors makes, far fewer than the critics imagine. There are legitimate arguments of course, and the report isn’t perfect. But the basic conclusions are far from being disproved. There was a 20 year review in 1992 and a 30 year final review in 2004. Both of these are bigger books than the original and engage in the various arguments and counter-arguments.

For more on how The Limits to Growth stands up today, see the CSIRO report mentioned above, or Matthew Simmons’ review. “There was nothing that I could find in the book that has even vaguely been invalidated” he writes.

Nice summary Jeremy you’ve covered it well.

Thank you for the review, I’m reassured. I haven’t read “Limits…” for a long time but I don’t remember it focusing on on stable equilibrium and support for the status quo, as Curtis claims in “All watched over…”, quite the opposite. I was and remain a supporter of “Limits…” and as a population modeler have always argued against the existence of stable equilibrium in multi-species ecosystems, there’s no contradiction. The term “balance of nature” refers to the fact that given half a chance fauna and flora persist long term, not to stable equilibrium in the mathematical sense.

Just watched that episode and I agree, Curtis doesn’t get this right. He says the report suggested stopping trying to change the world and keeping everything as it is, which it doesn’t. Neither do steady-staters believe that nature is stable. Still really enjoying ‘all watched over…’ all the same, despite not agreeing with some of it.

to check out the best common misconceptions, check out http://mrstoryteller7.blogspot.com/

I’ve just read Matthew Simmons’ review of LtG, written back in 2000. The whole way through, at point after point, I thought, “he’s right on the money”. Every single one of his predictions for the next decade were accurate. The *only* major development I can think of that he did not foresee was the explosion in natural gas production through non-conventional fuels, though it’s not like he rules this out. All this just makes his final paragraph chillingly depressing:

“Is there time to begin the thoughtful work which the Club of Rome hoped would take place post 1972? I would hope so. But, another 10 years of neglect to these profound issues will probably leave any satisfying solutions too late to make a difference. In hindsight, The Club of Rome turned out to be right. We simply wasted 30 important years by ignoring this work.”

“Every single […] were” –> “was”

Yes, we can’t say we weren’t warned, but the Rio negotiations show just how much of the Limits to Growth thinking has filtered through to our politicians. The answer is, unfortunately, none at all.

Being that I am the author of Beyond the Inflection Point: An Economic Defense of the Limits to Growth Theory, I obviously believe there is a limit to growth. In writing my book, I wanted to have a chapter devoted to background material on earlier limits-to-growth models and debates; from Malthus up to the Ehrlich-Simon wager. In reading the Limits to growth study I was dumbfounded that the price mechanism was lacking in the World3 model – which is not surprising being that none of the major researchers in that study was an economist.

Thinking that their updates would have addressed the shortcoming of the first edition, (perhaps by including price elasticities of supply and demand of resources), I read Beyond the Limits – up until page five,, or thereabout. Why did I stop. Because of an early graph found in that book..

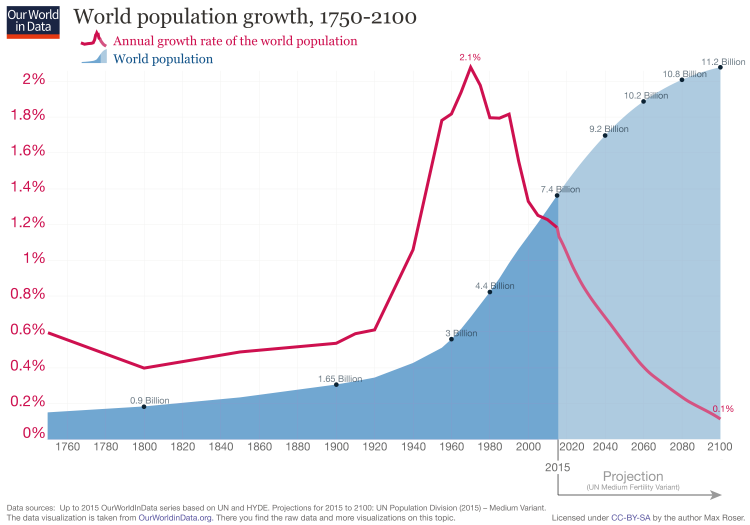

It showed that global population had not only been increasing up until the early 1990s, it had been increasing at an increasing rate. Being that escalating population growth was such a huge factor in Wrold3, how would of that model’s results been affected had it included population growth? The reason for mentioning this – and I think that Lex the demographic modeler could attest to this – is that global population growth has been increasing at a decreasing rate since the early 1960s. The relevance of this is that the global population graph presented in the book should have had an inflection point surfacing in the early 1950s – it should not have been shown as exponential growth. I’ll make my point with four questions:

1) Do you think that by the 1990s not one of the three PHds in that study was not aware of the fact that global population growth had started to slow down decades before Beyond the Limits was published?

2) Considering how slowing population growth would have seriously undermined certain aspects of their conclusions- in terms of pollution and resource depletion, do you think it was an honest mistake or an intentional misrepresentation?

3) Being that the lead researchers in the Limits to Growth and Beyond the Limits, were the Meadows, what might be inferred about the quality of research in the earlier work given the glaring non-trivial mistake regarding population growth found in the update?

4) Is it surprising that a serious neo-Malthusian like Herman Daly hardly makes reference to the Limits to Growth study in his many books?

In retrospect, it is difficult to know which did the most harm to the neo-Malthusian movement, Ehrlich’s lost wager to Simon, or the Club of Rome study. A final point. To what extent can we neo-Malthusians expect to be given credence by others if we if we are not willing to show the realness and due diligence needed to objectively critique our own literature? By parroting the half baked arguments found in the Limits to Growth and The Population Bomb, – without actually having objectively and independently evaluated them – those neo-Malthusians who think they are helping the cause are actually harming it. this is because they are the ones who are most likely to find egg on their face defending positions they don’t really understand.

Andrew

Line 17 should have read: “”… had it included slowing population…”Line 22 should read “…surfacing in the early 1960s – it…” The seventh to the last line should read “…due diligence needed to objectively critique [and proofread] our own literature [and posts]?”

Good questions. I don’t think there’s any deliberate attempt to mislead here. There’s obviously a distinction between population growth and the population growth rate. The growth rate has indeed been declining since the 60s. Population growth on the other hand, has continued to rise. (The multiplier may be smaller, but the base population on which it is operating is larger)

The graph on pages 4-5 is in the introduction and is simplified to demonstrate the point. It shouldn’t be seen as the final word on population – if you read on to chapter on that topic, you’d get the full picture. It explains that what we are talking about is the timing of a demographic transition, not endless exponential growth, and it mentions the fall in the growth rate.

That’s on page 23 in my edition. So maybe ditching it on page 5 was a bit premature!

As for Daly not mentioning the study, there’s no reason why anyone would need to keep mentioning it. It broke open the topic, but the scholarship and computer modeling that has followed is more relevant to anyone building on their work.