This week the price of gold burst through the $1,500 an ounce mark. It’s a new record in a long run for gold over the last five years.

This week’s spike is at least partly due, once again, to a credit ratings agency. Standard and Poor’s passed judgement on US debt on monday, and some investors have decided to move their money into gold instead. Gold is the classic fall-back investment, as the 2008 bump in the graph above shows. Any time the market switches from greed to fear, the price of gold rises.

Being fear-driven, it’s likely that it will promptly drop again, but in the longer term the trend will most likely carry on upwards. Why? Because while economists variously point to sovereign debt, inflation or the weaker dollar, there are non-economic factors in play. In particular, geological factors.

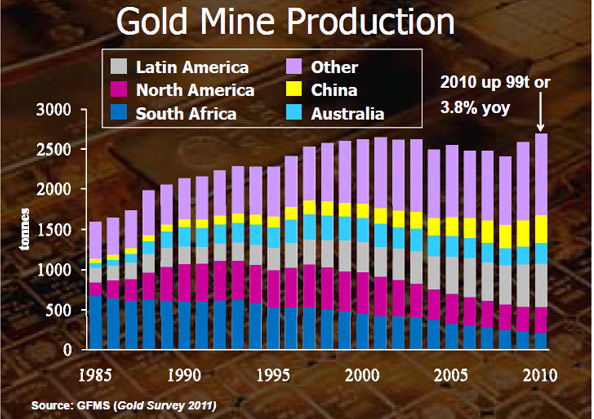

The annual GFMS Gold Survey for 2011 came out last week. It reports an all time high in gold production in 2010, but it comes after a decade-long decline. Despite the record prices over recent years, output from the world’s gold mines has hit a plateau. The industry has strained every sinew to raise production and capitalise on those high prices, but the gold just isn’t there to mine.

The record high for 2010 will no doubt give some commentators reason to believe that we’ve turned a corner, and production will begin to increase again. It may well do, as there are plenty of new projects ready to come online. But finding new gold is only half the challenge. The survey also records production costs, and the cost of bringing a tonne of new gold to market has gone up 20% on 2009. Gold now costs $857 an ounce to extract, as the easiest gold to mine is used up and the industry has to turn to more marginal sources and poorer quality ores. In 1950, you could expect 12 grams of gold per tonne of ore at the best mines. Today it is closer to 3 grams per tonne.

Runaway prices, a jagged plateau in the production curve, supply struggling to keep up with demand, rising production costs – this is a classic peak resource scenario.

What does peak gold mean for you and me? Probably nothing. The jewelry and electronics industry will have to turn increasingly to scrap gold. It is quite likely that the amount of gold bought for investment will overtake the amount bought for industry in the next few years, and that will mark an interesting transition. At that point, its perceived value becomes more important than its use value. There will be more people buying it to hoard than to make things with it, and it would be more speculative vehicle than tradeable resource.

The broader point is that all non-renewable, finite resources will at some point go into decline, and many of them matter more than gold. Oil production is on a similar plateau. Silver and Copper prices are at record highs, and while supply is just about keeping pace, there are signs of real desperation. The Chilean mine disaster was a case in point – a mine that was known to be dangerous, re-opened to cash in on the big profits to be made from the high copper price.

I’m not going to offer any predictions for peak metals, but when the writers of the Limits to Growth ran their development model in the 197os, they tracked the earth’s resource base from 1900 to 2100. They observed that if industrial growth continued, that resource base would begin to decline steeply around, well, right about now actually.