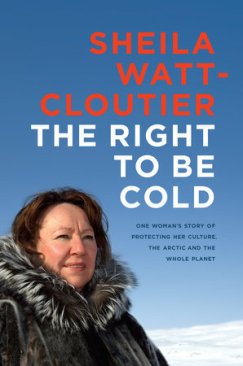

The Arctic is the front line of climate change. Because of global weather patterns, heat accumulates at the poles and the climate is changing twice as fast in the Arctic. The consequences are stark, and The Right to be Cold details them in this striking personal account of environmentalism in the North.

The Arctic is the front line of climate change. Because of global weather patterns, heat accumulates at the poles and the climate is changing twice as fast in the Arctic. The consequences are stark, and The Right to be Cold details them in this striking personal account of environmentalism in the North.

Sheila Watt-Cloutier is an Inuit activist, environmentalist and grandmother. Her childhood played out in the ‘old Arctic’ of hunting culture, dog sleds and igloos. Then she was relocated by the government for schooling, and lived back and forth between south and north Canada over the following years as she became a mother and pursued a career in education. Over the years she saw many changes, as trade increased, local customs eroded, snowmobiles replaced dogs, poverty increased and with it alcoholism, violence and social problems.

Watt-Cloutier worked in education and community organising, eventually running for office as head of the Inuit Circumpolar Council – an NGO that represents the 160,000 Inuit that live across Canada, Greenland, Alaska and Russia. It was here that, among other things, she became involved in environmental action.

Like the aforementioned heat, global weather patterns concentrate pollutants in the Arctic too. Watt-Cloutier became involved in the fight against Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), which were found in higher concentrations in the Arctic than anywhere else, even though Arctic communities contribute next to nothing to the problem – “there is no word in Inuktitut for toxins or pollutants” as the author notes. And yet, traditional foods that had made life possible in the Arctic for generations were now poisonous. Watt-Cloutier was an instrumental figure in advocating a global agreement on POPs, which was eventually signed in 2003.

Then came climate change, and it has profound impacts. For many of us, like me in Britain, climate change progresses virtually unnoticed. Not so in the Arctic: “we Inuit are the ground-truthers of climate change.” Permafrost thaws, and houses sink and tilt into the earth, leaving people homeless. Ice melts from underneath, making it impossible for travellers to tell if it’s safe to cross or not. Accounts of accidents on the ice begin to rise. When sea ice retreats, it brings polar bears closer to where people live, further compounding the danger. There are mosquitos in summer, disappearing lakes, unpredictable storms.

The changing conditions have knock-on effects for wildlife. Watt-Cloutier describes how chunks of ice used to scrape down the rivers, providing natural pruning for riverbank willow trees and stimulating new growth. Now it melts too fast, the new growth doesn’t materialise, and the Caribou that used to feed on the young willow shoots go hungry and thin.

And of course, in all of this there is a devastating human story. “Climate change was an issue of cultural survival,” as the author puts it. It’s hard to imagine no longer being able to trust the landscape you grew up in, or the foods you enjoy most. Local traditions become impossible. Old survival techniques don’t work any more – the snow is too soft and wet to build igloos much of the time now. “When you can’t find good snow in the Arctic”, Watt-Cloutier observes, “something is definitely wrong.”

In telling this story, Watt-Cloutier hasn’t needed to write a book about climate change. The Right to be Cold is her life story. The devastating effects she describes are just how things have unfolded in her town and amongst her community, and I found her story moving and humbling.

It’s also fascinating, and I was intrigued by the little details of an Arctic childhood, or descriptions of feasting, parenting, hunting traditions, all so very alien to my African upbringing. And then on top of that, there is Watt-Cloutier’s own inspiring story as an activist. After the success with POPs, she was involved in climate change negotiations, tirelessly traveling the world to bear witness to what was happening with her people and their homeland. She pioneered the rights-based approach that the title of the book hints at, bringing a human rights challenge from the Inuit people against the United States. It was widely reported at the time, broke open a new avenue for climate campaigning that many others have followed, and it garnered the author a Nobel prize nomination, a Right Livelihood Award and over a dozen honorary doctorates for her efforts.

In short, The Right to be Cold is an unusual and rather good memoir, from an extraordinary woman with a remarkable story to tell, and a warning to offer. As Watt-Cloutier writes, “the future of Inuit is the future of the rest of the world – our home is a barometer for what is happening to our entire planet.”

- The Right to be Cold is available from Earthbound Books UK and US.